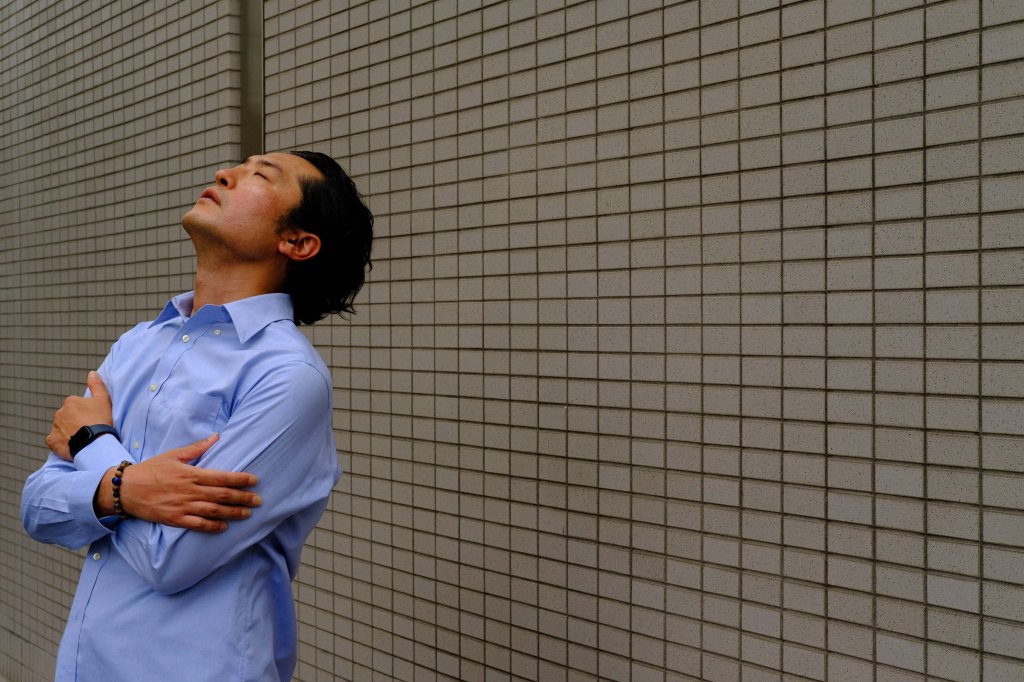

As part of the series “Social Misfits: Portraits from Japan”

Social Misfits: Portraits from Japan is a photo series and collection of interviews exploring what it means to stand outside the norms of Japanese society. Japan is often described as a country of harmony, order, and tradition — yet within that structure are individuals who choose a different path or choose to express themselves in ways that resist social norms.

We spoke to Junya about his experience living in Japan, and how he uses dance as a release. This story introduces Junya, who spoke to us about his life in Japan and how dance has become both a release and a form of resistance. For him, dance is a way to surrender, to heal, and to push back against the conformity around him. In his words, it is a practice of vulnerability and connection.

Scroll to view the full gallery and read our interview.

Full Gallery by Isabella Fowden

“Group harmony is great, but I cherish dissonance and noise as part of nature.” – JUNYA

How would you describe yourself in 3 words?

Junya: Three words? Nobody. I am nobody.

How would you describe Japanese society?

Junya: Systematic, super clean, and safe, I think. This society makes people very good at following rules, which is great, but quite often I feel that people in this society are bound too much by rules and lose sight of principles.

I recently read a book about Lafcadio Hearn, an Irish / Greek writer who emigrated to Japan around 1890-1900. He admired and struggled in Japanese society at that time, and described it as ants society, probably because of the Japanese virtue “cherish the harmony among people.” Group harmony is great, but I cherish dissonance and noise as part of nature.

“It is a practice to be vulnerable, surrender, and connect to surroundings.” – JUNYA

Do you think you fit into Japanese society?

Junya: I don’t know.

I sometimes have to express my demon inside; otherwise, I feel like a puppet in this society. This society wants docile puppets because they are useful in this system. If someone crosses the red light at the street, others follow. If there are many people queuing up, others follow. This is a very Japanese society, I think.

It is better to keep your opinions to yourself if you want to fit into this society, then you will be loved and can live happily, maybe. Unfortunately, I cannot live like this. I like to say what I want, and I like to listen to what people want.

The basic point is this mentality: before you express yourself, you watch others. If you recognise this, you feel “weird” or something, but there’s always a loophole to express yourself.

Do you feel immune to societal pressures?

Junya: I think I am influenced by societal pressures. I need to earn money to live and eat.

When I was younger I wanted a change of society, but now it’s more about finding a loophole. To find where to release or expose your own madness, or I would like to say barbaric energy. Like dance, I like to dance in a unique way. I feel nobody but I don’t feel like I’m an invisible person.

What does dance mean to you?

Junya: Healing is for sure. First of all, I have to heal myself. I can forget about the conscious self in the frame and connect to something when it is good. When it is bad, it just shows ego and is miserable. It is a practice to be vulnerable, surrender, and connect to surroundings. I like this practice and want to continue.

Sometimes it can affect others; I don’t say I’m healing others by dancing. But sometimes I dance and people react. Recently, when I joined a performance, an audience member who was crying a bit talked to me afterward, and I felt that dance has such potential to communicate emotions. I don’t want to say therapy, but healing or purification to be empty self, unity.

What’s one thing that you would want people to know about you?

Junya: I grew up in Mexico and Canada, when I was 2– 8. My identity is very distorted. So, it’s not easy, but in Europe there are a lot of people like that, there’s a way to positively exist in that unstable identity. In order to do that I tell myself I always have to create something. I think it is positive now. When I’m performing I don’t need to think about anything like that.

As a dancer, I lived in Hungary and worked in a theatre company in Vojvodina region in Serbia. Spending time with artists who experienced the Yugo war period and being refugees completely changed my life and gave me strength to believe in this unstable existence.

I told myself not to be a Japanese “cherishing the harmony among people” without caring about the existence of refugees.

Do you hope to stay in Japan?

Junya: I think I will get out soon. Japan is a beautiful country, and I am working on picking up what is good here now. Not a negative feeling, but I think I will.

Leave a Comment